It’s hard to believe it was over two years ago I wrote, “I’m Hearing A Lot Of Smart People Use ‘The Four Most Dangerous Words In Investing’ These Days.” At the time, I was concerned by the fact that a number of the financial minds I respect most were all falling into the same, dangerous bull market trap of believing “this time is different.” A few months later the stock market experienced its first real correction in years, not just once but twice, and these calls died away. But stocks rallied strongly out of those lows and now they’re back again.

This time it’s some of the most respected minds in the world propagating theories of a “new era” for risk assets. Jeremy Grantham recently wrote a piece arguing that both equity valuations and profit margins have possibly reached a new, higher plateau:

Of all these many differences, the most important for understanding the stock market is, in my opinion, the much higher level of corporate profits. With higher margins, of course the market is going to sell at higher prices. So how permanent are these higher margins? I used to call profit margins the most dependably mean-reverting series in finance… In a world of reasonable competitiveness, higher margins from long-term lower rates should have been competed away. (Corporate risk had not materially changed, for interest coverage was unchanged and rate volatility was fine.) But they were not, and I believe it was precisely these other factors – increased monopoly, political, and brand power – that had created this new stickiness in profits that allowed these new higher margin levels to be sustained for so long.

Grantham has clearly changed his mind about the phenomenon of mean-reversion in the markets. At the very least, he is questioning his own faith in the reliability of this phenomenon. I think Sir John Templeton, the man who coined the phrase in the title of this piece, would simply respond by saying that trends are most likely to reverse just as everyone gives up on the idea of them ever reversing again. Interestingly, my friend Dr. John Hussman recently demonstrated that this is very likely the case in this example.

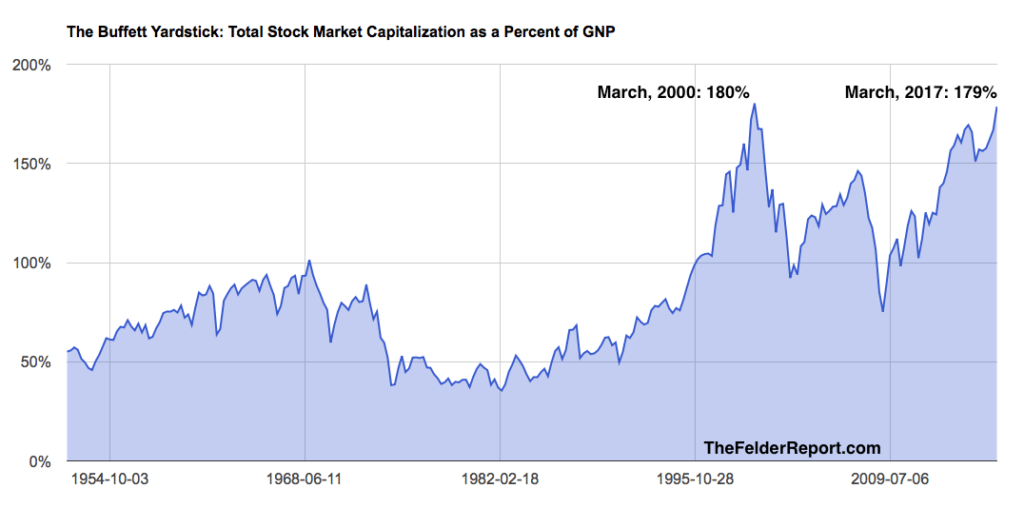

Another example of “this time is different” comes from one many consider to be the greatest investor of all time. Warren Buffett has famously said many times, “the price you pay determines your rate of return.” Additionally, he wrote back in 2001 the best measure of equity valuations was total stock market capitalization as a percentage of GNP: “For me, the message of that chart is this: If the percentage relationship falls to the 70% or 80% area, buying stocks is likely to work very well for you. If the ratio approaches 200%–as it did in 1999 and a part of 2000–you are playing with fire.”

Above is a chart of this measure I put together using data from the Fed. It shows the dotcom mania peak in this ratio was 180%. Today, it stands at 179%. So with valuations matching their all-time bubble peak, is Buffett telling investors they are once again “playing with fire”? Not even close. In fact, he’s not only telling them it’s not a bubble but that stocks actually look “cheap.” What gives?

Well, he’s found a new “most important metric” which seems to be the level of interest rates. In other words, valuations don’t matter as much as they did in the past because “this time is different” in that interest rates are so low. I find this fascinating because the idea of low interest rates justifying high equity valuations has been debunked by many including Cliff Asness (“Fight the Fed Model“) and the Federal Reserve, itself (“Inflation-Induced Valuation Errors in the Stock Market“).

I think Charlie Munger was probably a bit more candid, as he is prone to being, when he said at the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting recently, “The investment world has become more complicated. We can’t bring back the low hanging fruit we will have to reach for higher branches.” So much for demanding a “margin of safety” or waiting for a “fat pitch” or any of the other axioms Buffett made famous over the past half-century.

Is it truly different this time? Certainly, there are a lot of smart folks who seem to think so. Still, I continue to believe that the only real difference is in the way that the present rhymes with history rather than actually repeats it. And, as Sir John Templeton taught us, when so many deny the lessons of history it usually means they’re just about to learn them all over again. Time will tell.